Occupational Therapy – About the Concept of Occupational Competence

The approach of action theories to understand human occupation in its physical and psychical dimensions made the School of Occupational Therapy Biel use models of action theory as models of thought in order to gain a more in-depth theoretical understanding of occupational therapy.

Action theories attempt to record, analyze and show the visible, external behavior and the corresponding internal, cognitive and at times emotional processes – processes of cognition, thought and experience. Researchers such as Levin (1969), Leontjev (1987) and Hacker (1986) above all focused on examining the connection between cognition and action. More recently, action theorists such as Volpert (1983) have increasingly introduced emotional processes into the existing models. Von Cranach (1980) attempts to include social processes and interactions in the action theories.

To date, most models of occupational therapy have been developed in the Anglo-Saxon world (Kielhofner, Canadian Model of Occupational Performance CMOP, 1997, Australian Occupational Performance Model OPM, 1998). German translators of these models have encountered the problem of how to accurately convey the meaning of the term «occupation.» In German texts, the term is often translated as «Betätigung.» Based on the terminology used in existing action theories, the Biel Model refers to the occupational competence of a human being, of action and of actions.

In action theories, activities are referred to as occupations with which humans influence their environment in a conscious and goal-oriented way. A person’s occupational competence is shaped by personal possibilities and the specific conditions of his/her surroundings.

Several factors characterize human occupation

(Hacker 1986/1995, Leontjev 1980, Volpert 1980, Schüpbach 1995):

- Occupations* are goal-oriented and conscious (see above)

Occupations require the ability to develop a possible target state in the imagination.

Occupational goals refer to reality when they take into consideration personal possibilities and the decisive and specific environmental conditions. Occupations have varying degrees of consciousness: They can range from overall planned, controlled occupations to automatic routines or habitual behavior. - Occupations are motivated

Motives for occupations may be based in personal, social or factual meanings.

In all motives for occupations, the subjective orientation and the orientation specific to a culture are of utmost importance. - Occupations are structured

Occupations comprise a construction (based on a plan of occupation), a sequence and a conclusion. Occupations are steered towards the conscious goal and regulated accordingly. The results of the occupation are then assessed. Many such occupational sequences can be interrupted, restarted or, if necessary, aborted. - Occupations are self- or co-determined or determined by third parties

Occupations can be self- or co-determined or determined by third parties. Co-determination includes gradual combinations of self and foreign determination. Instructions, orders and task allocations can be examples of occupations determined by a third party. - Occupations shape humans and their environment

Humans shape their environment with their occupations. Yet occupations also influence the person who acts: Occupations form the actor. In all the different areas of life, humans meet not only a wide range of occupational possibilities but also occupation-related expectations (See 1.6. Areas of Life)

*We understand occupations as actions that have been substantiated and relate to areas of life..

A person’s occupational competence develops and changes during lifetime

Over the course of a child’s socialization and individuation, its most simple occupational patterns become differentiated and are grouped into more complex units. The structures, shapes, scope and effects of occupations change during an individual’s lifetime. Occupations become increasingly differentiated and, through repetitions, more fluid and varied. In the elderly, however, it can be observed that occupations can also be «reduced to a minimum» or disintegrate.

We largely learn the concept of occupation through occupations in real-life situations or at least through test occupations in trial situations that are close to reality. In a child in particular, the mental structures that lead to occupations are the result of the occupations themselves and the internalization that leads to mental occupations (Piaget, 1971). Learning with models (Bandura, 1973) can support this process.

Sickness and disability as well as an environment that demands too much or too little impair or hinder a person’s occupational competence

A person’s occupational competence can be hindered, to varying degrees, by sickness and/or disability. External requirements and expectations that demand too much or too little of a person can also impair occupational competence. The impairment of occupational competence in the sense of inactivity can lead to physical and mental changes, to the loss or reduction of capabilities and to the dissolution of habits and temporal structures.

Occupational competence as the goal of occupational therapy

Occupational therapy is a profession concerned with promoting health and well being through occupation. The primary goal of occupational therapy is to enable people to participate in the activities of everyday life. Occupational therapists achieve this outcomes by enabling people to do things that will enhance their ability to participate or by modifying the environment to better support participation. (World Federation of Occupational Therapists – Definition 2004)

Occupational therapy is a profession concerned with promoting, maintaining and/or restoring people’s ability to act. Occupational therapy is based on the premise that a person’s ability to carry out actions/occupations that are meaningful for him/her is positively correlated with his/her health. (Job profile occupational therapy, 2005 – ASSET – EVS)

Occupation as a means of therapy

Occupational therapy uses occupations as means of therapy. According to the underlying concept of occupational therapy, being occupied is a basic human need. Furthermore, the concept assumes that therapeutic effects can be achieved by preparing for and exercising select and appropriate occupations, by reflecting upon these occupations and by evaluating their results. In occupational therapy, the therapist supports the patient in developing ways to cope with his/her environment. If necessary, the therapist also tries to adapt environments to the specific possibilities of the patient

Factors That Determine Occupations

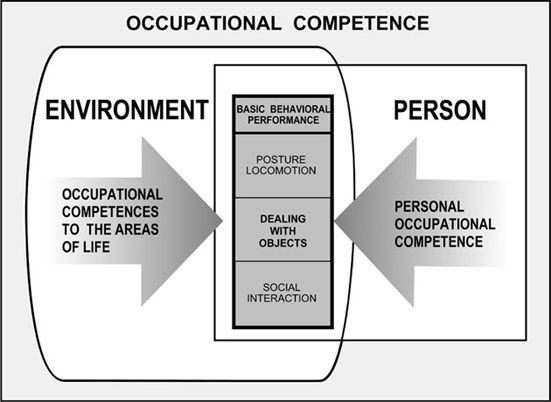

A person’s occupational competence is determined by personal factors and factors related to areas of life (see above).

We consider the personal factors that determine occupations to be a person’s individual possibilities and difficulties to act. The factors related to areas of life that determine occupations, meanwhile, are the situational requirements and the possibilities that arise from occupation-related offers coming from a person’s environment. In all domains of the Biel Model, we describe the possibilities and difficulties a person faces. We believe that, even in sickness, disability or old age, people continue to have possibilities to act that must be met according to the remaining possibilities.

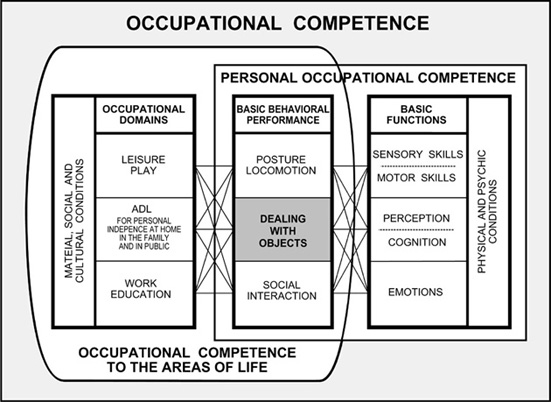

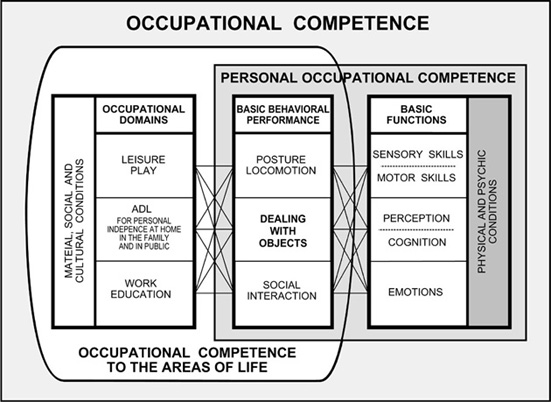

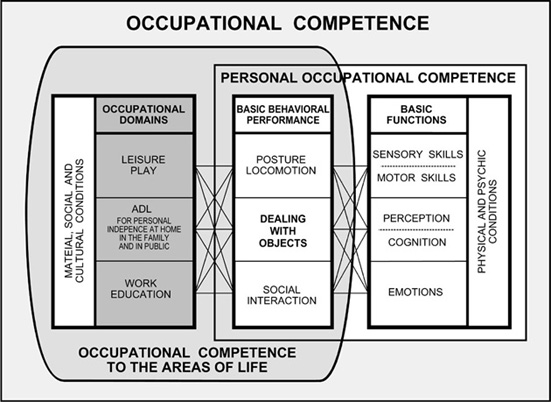

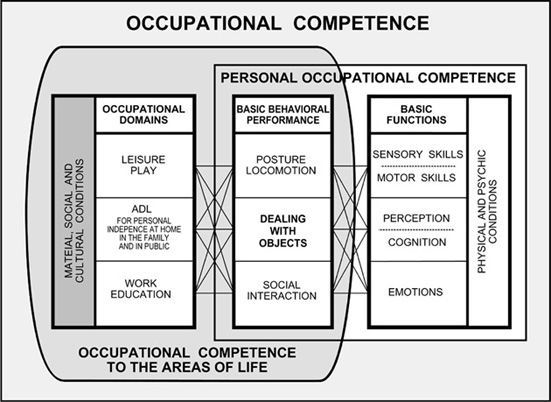

In the diagram of the Biel Model, the personal factors and the factors related to areas of life that determine occupation overlap. It is this overlapping area to which we have assigned the factors that determine occupational competence (see diagram No. 2).

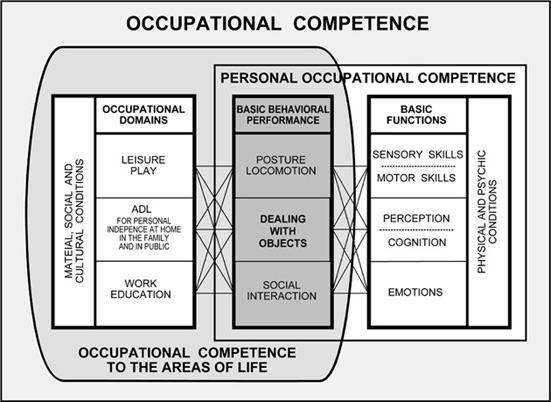

Basic Behavioral Performances

Basic behavioral performances (see diagram No. 3) are a visible kind of behavior that can be observed from a person’s own and from an outsider’s perspective and are determined both by the environment and the individual him/herself. Consequently, behavioral performance is always influenced by situational requirements related to an area of living and by possibilities and difficulties specific to an individual. We consider the domains «posture/locomotion,» «dealing with objects» and «social interaction» to be a part of behavioral performance.

All these domains are seen as interactions between an individual and his/her environment: «Posture/locomotion» is the interaction between an individual and space and gravity, «dealing with objects» comprises any interaction between an individual and the objects available in his/her environment, and «social interaction» is the interaction between an individual and the social environment. Occupations always consist of components of these three domains

Posture/Locomotion:

We define posture as the posture of the human body in concrete space and dependent on gravity. Furthermore, the definition also comprises a person’s capability to change and adapt his/her posture.

Locomotion is needed to change the body’s location in spaces

Dealing with objects:

Occupations are oriented towards objects (Levontjev, 1983). This can mean dealing with objects or also manufacturing objects. Objects are cultural products of societies, and it is through society that they obtain their importance and value. An individual can only share the experience of objects and orient its occupations towards them if it acquires the occupational possibilities that a culture has in mind for a certain object. A child acquires the culturally-defined use of objects through occupations it pursues while growing up (Oerter, 1993). Internal occupation – occupations pursued mentally – is also oriented towards objects (Piaget, 1975). Occupational therapy seeks to support and enable a patient’s occupational competence in these aspects.

Social interaction:

Possibilities and difficulties specific to an individual are determined by his/her social abilities (e.g. empathy, communicational and cooperational abilities, knowledge of current and binding social norms and rules and their appropriate inclusion in occupations), by social skills (e.g. greetings, getting in contact) and by social attitudes and values (e.g. willingness to communicate and cooperate, the offer and acceptance of social support).

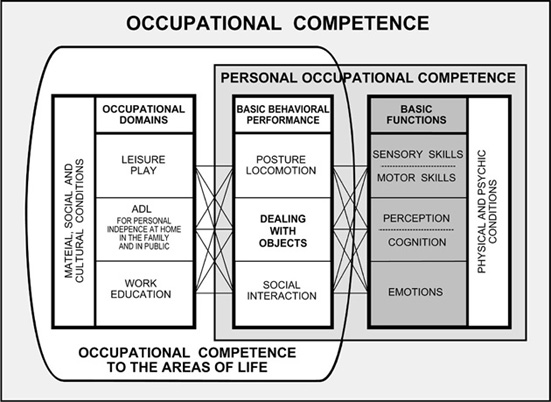

Basic Functions

For us, the basic functions (see diagram No. 4) are a construct. They are an arrangement and allocation of single functions that are connected and highly correlated. Looked at in an isolated manner, these functions cannot really be grasped. A person’s behavior in a concrete situation can be observed particularly well: His/her posture and locomotion, the way he/she deals with objects and his/her social interactions. However, the basic behavioral performance allows us to draw conclusions about a person’s sensory and motor functions, perception, cognition and emotions. The basic behavioral performance and the basic functions are closely correlated. It is not possible to look at and influence one aspect without taking the other into consideration.

Basic Sensory and Motor Functions:

Basic sensory functions are the reception of data via the sense organs. Sensory functions comprise the olfactory, gustatory, optic, acoustic senses as well as the vestibular, tactile and proprioceptive senses. Several theoretical approaches (see Gibson, 1973) point out that sense organs also search for data «independently.»

Basic motor functions are movements carried out by the body. They comprise mobile and static components. The movements serve as a means for the body or a body part to move from one location to another. Key elements of a person’s motor functions are the static and dynamic fine and large motor functions as well as motion coordination.

Basic Perceptive and Cognitive Functions:

Basic perceptive functions are the selection of information that derives from the data taken in via the sensory receptors. Perception is an active process that serves to set up and construct a figure, shape or structure. It is an extraordinarily fast process.

Of the vast array of signals that streams into the organism, the ones that are related to an occupational goal need to be filtered out. In this process, the physical intensity is less decisive than the active selection the organism makes. Based on prior experience, the organism will «search» a certain signal pattern and seek to form an impression of the environment that is established through the comparison to past experience.

We obtain signals through occupations and processes. Features characterize objects. When using perception, we look for characteristics and signals that allow us to define objects or situations. For us, perception includes olfactory, gustatory, visual and auditory perception areas, as well as vestibular, tactile/kinesthetic and proprioceptive perception areas.

The basic cognitive functions are forms of information processing. Cognition is a wide-ranging term that refers to the ways in which humans understand events in their «Lebenswelt,» perceive personal experiences and remember them. Cognition describes the mental processes or the way an individual performs all active internal structuring and re-structuring of situations, problems and concepts (identification, analyses, syntheses, evaluations, etc.). Important areas of occupation-related cognition are: an individual’s understanding of objects, goal-oriented situational analysis and occupational regulation as well as (short and long-term) memory and concentration/attention.

Basic Emotional Functions:

Basic emotional functions are functions that are related to an individual’s emotional experience and the corresponding reactions. Emotions can be differentiated on the basis of their intensity, quality and temporal sequence. In our model, affects are intense, immediate and usually short-lived emotional expressions and the corresponding emotional reactions, while mood is a long-term, very emotional state of mind. Important occupation-related emotions are the emotional involvement in planning, carrying out and evaluating an occupation, motivation and frustration tolerance.

Physical and Mental Conditions

Physical and Mental Conditions

Physical and mental conditions (see diagram No. 5) refer to person-related factors that influence or determine a person’s individual occupational competence in his/her basic functions and behavioral performance. Age, sex, height, body proportions, weight, constitution and mental dispositions are some of these factors.

The possibilities and difficulties in the basic functions as well as the physical and mental conditions strongly influence an individual’s achievements in basic behavioral performance.

Yet a person’s occupational competence is not solely influenced by personal conditions, but also by the occupational domains, in other words the possibilities and requirements in the various areas of life as well as the material, social and cultural preconditions.

Occupational Domains

Humans act in a variety of ways in different occupational domains.

In our culture, we make a distinction among three areas of life: «activities of daily living» (personal independence at home, in the community of life and in public), «work and education» and «leisure and play» (diagram No. 6). These different areas are strongly characterized by the respective material, social and cultural environment. In each and every area of living, an individual encounters a range of occupational possibilities. Occupational possibilities are behavioral sequences that are goal-oriented and tied to rules. They enable or demand culturally accepted or called-for sets of behavior (Kielhofner, 1995).

Occupational possibilities offer a person a range of possibilities as to how to cope with and organize his/her environment. Individuals assume occupational possibilities and usually carry them out within a culturally accepted range. However, the expectations a person’s social environment has in terms of how select occupations in certain situations are to be carried out can exert a great deal of pressure on him/her. The boundaries between activities of daily living and work-related or leisure activities are perceived subjectively; some will experience them as fluid.

Activities of daily living (ADL)

The area «activities of daily living» describes activities that serve the individual’s self-support or the support of third parties. It comprises everyday activities at home and in public. Usually, people have a choice as to when, where, to what extent and how often they carry out their activities of daily living. In the course of a lifetime, these activities are transformed from simple partial activities to differentiated and more complex occupational forms. Depending on the social and cultural meaning, these activities can include work characteristics.

Work / education

Work / profession is determined by the carrying out of job-related activities that usually define a person’s work or profession. The carrying out of such occupational forms generally serves to ensure the material foundation for the person’s life, or that of the family members the person is responsible for. In many professions, people’s choice of occupational forms is rather limited. Having a greater choice, however, can considerably improve motivation and job satisfaction (Schüpbach, 1995).

Education is also part of this area. Education helps a child to, for instance, develop specific occupational forms that are typical for his/her cultural area. In education, individuals learn the occupational competence for a variety of occupational forms that they will subsequently carry out.

Leisure / play

Occupational forms that cannot be allocated to the areas of «activities of daily living» and «work» normally fall into the area of «leisure.» Generally speaking, leisure helps an individual relax after the experiences and demands of the other areas. When planning what to do in their «spare time,» people tend to have more freedom to choose than in the other two areas.

For adults, play can be a form of organizing one’s leisure time. The boundaries between leisure, play and work are subjectively perceived as fluid. For children, however, play can almost assume a «near-job» character: By playing, they learn or differentiate competencies and skills that will form the foundation of future learning in all areas of life.

Material, Social and Cultural Conditions

The material, social and cultural conditions (see diagram No. 7) are correlated in a complex manner: They influence and are dependent on one other. Material, social and also cultural conditions influence the occupational competence of an individual in his/her various areas of life.

Material conditions

Material conditions are temporal and spatial conditions, objects and materials as well as financial requirements. Important factors that influence occupations are: light conditions, sounds/noise pollution, ventilation, resistance of materials, temperature, quality of the tool being used, condition and stability of the work surface as well as risk potential.

Social conditions

Social conditions are, for example, social norms, demands and expectations of third parties as well as offers of social support. They can be represented by individuals or exist in the form of universal norms and expectations. Social conditions are influenced by cultural conditions.

Cultural conditions

Cultural conditions are the totality of habits, attitudes and institutions that are related to family, state form, economy, work, ethics, legal system, thoughts, art, religion and the like. Cultural conditions are closely related to the community in which they are applied or carried out.

The Biel Model presents a subtly differentiated structure used to describe human occupations, which are seen as the interaction between an individual and his/her environment.

Literature

Autorenteam der Schule für Ergotherapie Biel (Béguin H., Dreier S., Mosthaf U., Nieuwesteeg M-Th., Schüpbach H., Somazzi M., Versümer G.). (1995). Das Bieler Modell – ein Modell zum Entwickeln und Evaluieren ergotherapeutischer Massnahmen. Fachzeitschrift des ErgotherapeutInnen Verbandes Schweiz, Nr. 9

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Schweizerischen Schulen für Ergotherapie (ASSET) und ErgotherapeutInnen-Verband Schweiz (EVS) (2005). Berufsprofil Ergotherapie. Unveröffentlichtes Arbeitspapier

Bandura, A. (1969). Principles of Behavior Modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT) (1997). Enabling Occupation – An Occupational Therapy Perspective. Ottawa, Ontario: CAOT Publications ACE.

Cranach, M. von, Kalbermatten, U., Indermühle, K. & Gugler, B. (1980). Zielgerichtetes Handeln. Bern: Huber.

Chapparo, Ch., Ranka, J. (1997) Das Occupational Performance Model OPM Australia. Unveröffentliches Unterrichtsskript, Schule für Ergotherapie Biel.

Dorsch, F. (1987). Psychologisches Wörterbuch. 11., ergänzte Auflage. Bern: Huber.

Gibson, J. (1973). Die Sinne und der Prozess der Wahrnehmung. Bern: Huber.

Hacker, W. (1986). Arbeitspsychologie. Bern: Huber.

Hacker, W. (1995). Handlungsregulationstheorie. Universität Bern. Reader zur Vorlesung

Hagedorn, R. (2000). Ergotherapie – Theorien und Modelle. Die Praxis begründen. Stuttgart: Thieme.

Herrmann, T. (1984). Handbuch psychologischer Grundbegriffe. München: Kösel.

Jerosch-Herold, Ch., Marotzki, U., Hack, B.M. & Weber, P. (1999). Konzeptionelle Modelle der ergotherapeutischen Praxis. Berlin: Springer.

Kielhofner, G. (1995). A Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application. 3rd ed.. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Krieger, D. (1996). Einführung in die allgemeine Systemtheorie. Paderborn: Fink.

Leontjew, A. (1982). Tätigkeit, Bewusstsein, Persönlichkeit. Berlin: Volk & Wissen.

Lewin, K. (1969). Grundzüge der topologischen Psychologie. Bern: Huber.

Mosey, A. C. (1981). Occupational Therapy – Configuration of a Profession. New York: Raven Press.

Oerter, R. (1993). Psychologie des Spiels. Weinheim: Beltz.

Piaget, J. (1975). Das Erwachen der Intelligenz beim Kinde. Stuttgart: Klett.

Piaget, J. (1975). Nachahmung, Spiel und Traum. Stuttgart: Klett.

Scheepers, C., Steding-Albrecht, U. & Jehn, P. (Hrsg.) (1999). Ergotherapie – Vom Behandeln zum Handeln. Lehrbuch für die theoretische und praktische Ausbildung. Stuttgart: Thieme.

Scheiber, I. (1995). Ergotherapie in der Psychiatrie. 2. Auflage. Köln: Stam.

Schüpbach, H. (1995). Grundlagen der psychologischen Handlungstheorie für die Ergotherapie. Unveröffentlichtes Arbeitspapier Schule für Ergotherapie Biel.

Schule für Ergotherapie Biel (1998). Tätigkeitsbeschreibung Ergotherapie. Internes Arbeitspapier.

Volpert, W. (1983). Handlungsstrukturanalyse als Beitrag zur Qualifikationsforschung. Köln: Pahl-Rugenstein.

World Federation of Occupational Therapists – Definition 2005. http://www.wfot.org. (Juni 2005).